Archaeologists have discovered a rare Iron Age helmet in Norfolk

In Snettisham, one of England’s most significant archaeological sites, advanced scientific tests have revealed that fragments of copper alloy are parts of an extremely rare Iron Age helmet. The British Museum conducted a 15-year project to examine a treasure trove of 14 gold, silver, and bronze torcs (twisted metal rings worn as jewelry) discovered between 1948 and the 1990s, leading to this astonishing find.

Located near Hunstanton, Snettisham has yielded numerous valuable artifacts on a wooded slope overlooking the northwest Norfolk coast. This area is referred to as the “gold field,” and the discoveries made here represent one of the densest concentrations of Celtic art. Known as the “Snettisham Hoard,” these artifacts were buried in at least 14 different deposits between 150 BC and AD 100, spanning the Late Iron Age and Early Roman periods.

Dr. Julia Farley, the Iron Age curator at the British Museum, emphasized the uniqueness of this helmet fragment, noting that only about ten Iron Age helmets have been found in Britain, each with its distinct characteristics. Additionally, the confirmation that Iron Age metalworkers perfected the art of mercury gilding—applying gold to bronze using a toxic mercury-gold mixture—was one of the most surprising findings. This technique was employed in the creation of both the helmet and the extensive collection of torcs from Snettisham.

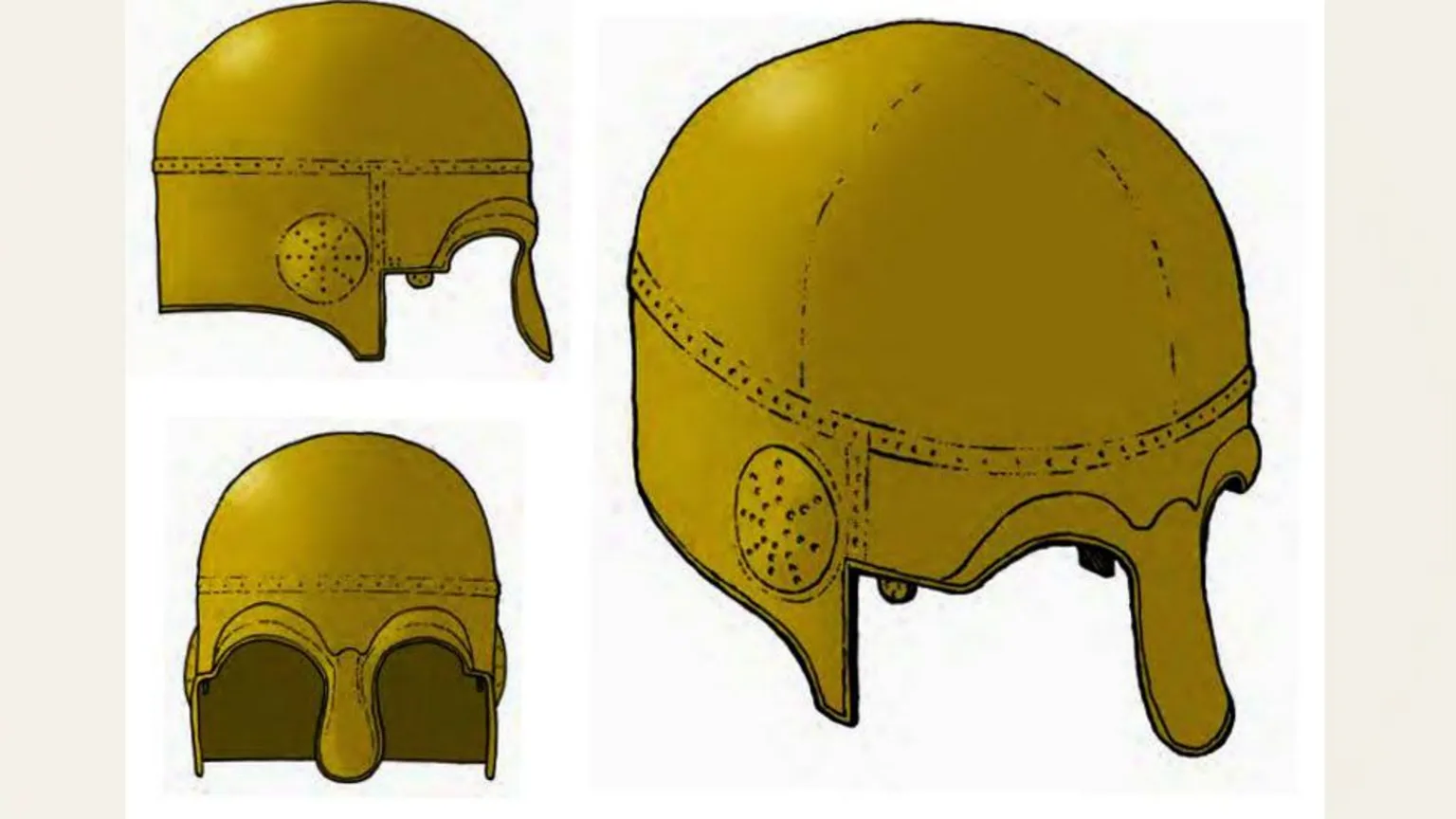

Dr. Farley stated, “The reason everyone in that room was so astonished… Iron Age helmets from pre-Roman Britain are incredibly rare.” She highlighted the helmet’s extraordinary nasal bridge and the finely hammered bronze plates, which required exceptional skill to create. “We didn’t know they could do this in Britain 2,000 years ago.”

Dr. Jody Joy, a former curator of Iron Age Europe at the British Museum and a key researcher on the project, explained that the helmet fragments, previously thought to be parts of a ship, had long been considered one of the unsolved mysteries of the Snettisham Hoards. The materials were meticulously reassembled by metal conservator Fleur Shearman, piecing together a complex archaeological puzzle.

Researchers believe the helmet was likely incomplete when buried, as many components were missing. Dr. Joy speculated that it may have been hidden for personal or emotional reasons and could have been used to carry other items, such as torcs.

Around 400 torcs have been found in the fields and woods near Ken Hill, indicating that these artifacts could have been worn as neck, arm, or bracelet rings. Among the most complex gold artifacts from ancient world excavations is the Snettisham Great Torc, which was found almost complete among more than 60 rings.

The British Museum initiated this extensive research project in collaboration with Norwich Castle Museum, as the torcs had remained largely unstudied for many years.

Using advanced scientific analyses, including electron microscopy, researchers were able to uncover intricate details about the torcs, such as wear and polishing in areas that came into contact with the body or clothing. They concluded that the wear and tear on these valuable items indicated they had been worn for a long time by their owners.

The team confirmed that torcs were likely worn not only by high-status men but also by women and even younger individuals. Dr. Farley remarked, “Torcs are unique; they are individual, and you wear them on your body, whereas coins are indistinguishable. You can give them to many people, and they can be distributed and returned. Our theory is that these torcs were too special, unique, and significant to be melted down into coins, so instead, people decided to hold a ceremony to bury them together.”

Cover Image Credit: A recreation by artist Craig Williams showing the nose and eyebrow pieces that first alerted an expert that the fragments might be a helmet. Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply