Surgical scars on a 9500-year-old skull found in the Aşıklı mound in Anatolia caused great astonishment in the scientific world. Now there are signs that cancer was treated in the scars seen on a 4000-year-old Egyptian skull.

A USC-led study reveals possible attempts to treat cancer in a 4,000-year-old Egyptian skull.

Cut marks on the skull may indicate that doctors in ancient Egypt tried to operate on skin overgrowth or learn more about cancerous disorders after a patient’s death.

The research team, led by researcher Ramón y Cajal from the Department of History at the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC), Edgard Camarós, was surprised by the discovery of cut marks around carcinogenic growths in an ancient Egyptian skull, which allowed them to develop new ideas about how ancient Egyptians treated disease. They believe these findings provide evidence that ancient societies were attempting to discover and operate on tumors thousands of years ago.

“This finding is unique evidence of how ancient Egyptian medicine tried to treat or discover cancer more than 4,000 years ago,” added the study’s lead author, paleopathologist Edgard Camarós, “this is an extraordinary new perspective in our understanding of the history of medicine.”

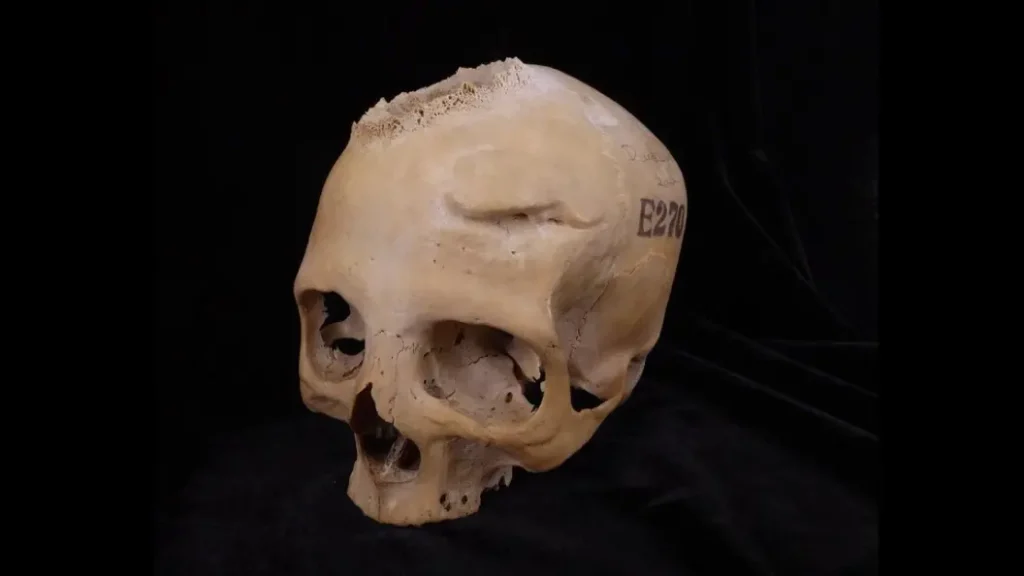

“We wanted to know the role of cancer in the past, the prevalence of this disease in antiquity and how ancient societies interacted with this pathology,” said Tatiana Tondini, a researcher at the University of Tübingen and co-author of the study published in Frontiers in Medicine. To this end, the research team examined two skulls preserved in Cambridge University’s Duckworth collection. Skull and jaw 236, dating from 2687 to 2345 BC, belonged to a man between 30 and 35 years old, while skull E270, dating from 663 to 343 BC, belonged to a woman over 50 years old.

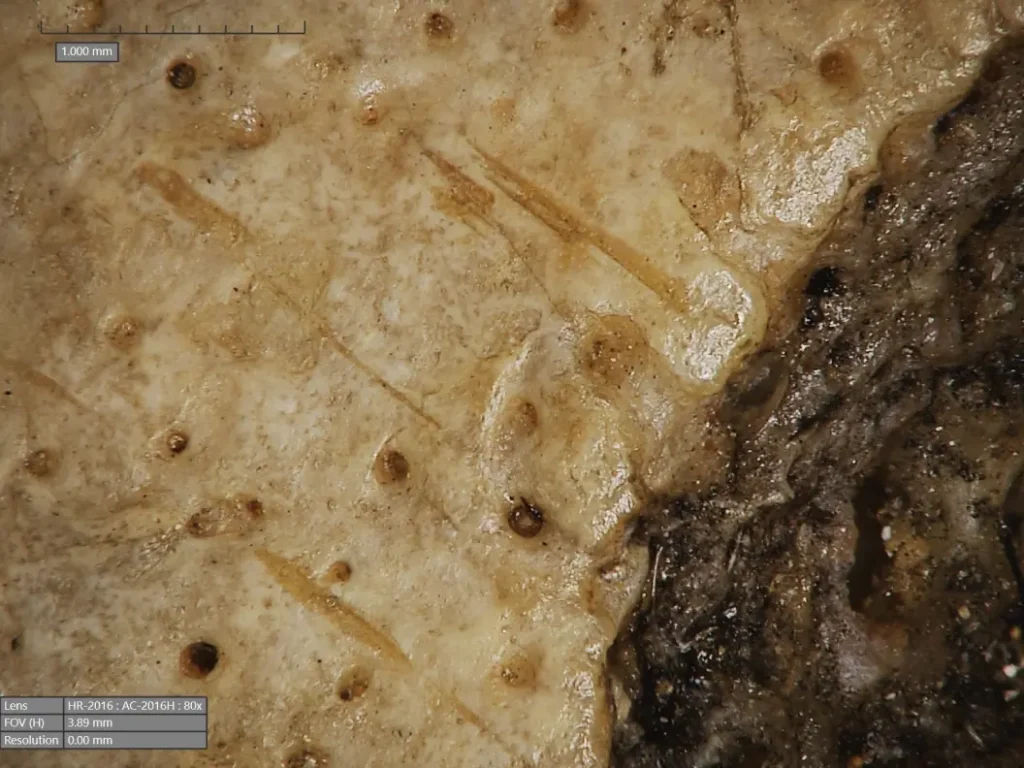

In skull 236, microscopic observation showed a large lesion consistent with excessive tissue destruction, a disease known as neoplasm. In addition, there are approximately 30 small, round metastatic lesions scattered throughout the skull.

What surprised the team was the discovery of cut marks around these injuries, possibly made with a sharp object such as a metal tool. “It seems that the ancient Egyptians performed some kind of surgical intervention related to the presence of cancer cells, and ancient Egyptian medicine also seems to indicate that they performed experimental treatments or medical screenings related to cancer,” says co-author and professor Albert Isidro, an oncology surgeon at Sagrat Cor University Hospital who specializes in Egyptology.

According to ancient texts, the research team knows that – for their time – the ancient Egyptians were highly skilled in medicine. For example, as Edgard Camarós notes, they could identify, describe and treat traumatic diseases and injuries, make prostheses and insert dental shutters. Other diseases, such as cancer, could not cure them, but they could try. Studying the limits of trauma and oncology treatments in ancient Egypt, the USC-led team examined these two human skulls, each thousands of years old. And they found that although ancient Egyptians could treat complex skull fractures, cancer was still a limit of medical knowledge.

The cancer E270 skull shows a large injury consistent with a cancerous tumor leading to bone destruction. This may indicate that, in the team’s opinion, cancer was a common pathology in the past, despite the fact that with the current lifestyle, people are getting older and cancer-causing substances in the environment increase the risk of cancer. This skull also has two healed wounds from traumatic injuries, one of which appears to result from a violent incident at short range using a sharp weapon. These healed injuries could mean that the individual potentially received some form of treatment and survived as a result, they contribute to the study coordinated by Camarós.

However, it is rare to see such a wound in a woman, and most violence-related injuries are found in men. “Was this woman involved in some kind of combat activity?” ask the research team, noting that if so, it would be necessary to rethink the role of women in the past and how they actively participated in conflicts in antiquity.

However, the team noted that the examination of the bone remains faces some challenges that prevent definitive conclusions, especially since the remains are often incomplete and there is no known clinical history. In archaeology, they note, one works with a fragmented piece of the past, which makes an accurate approach difficult.

“This study contributes to a shift in perspective and lays an encouraging foundation for future research in the field of paleooncology, but more work will be needed to reveal how ancient societies treated cancer,” Camarós said.