A 7000-year-old Neolithic settlement discovered in Serbia

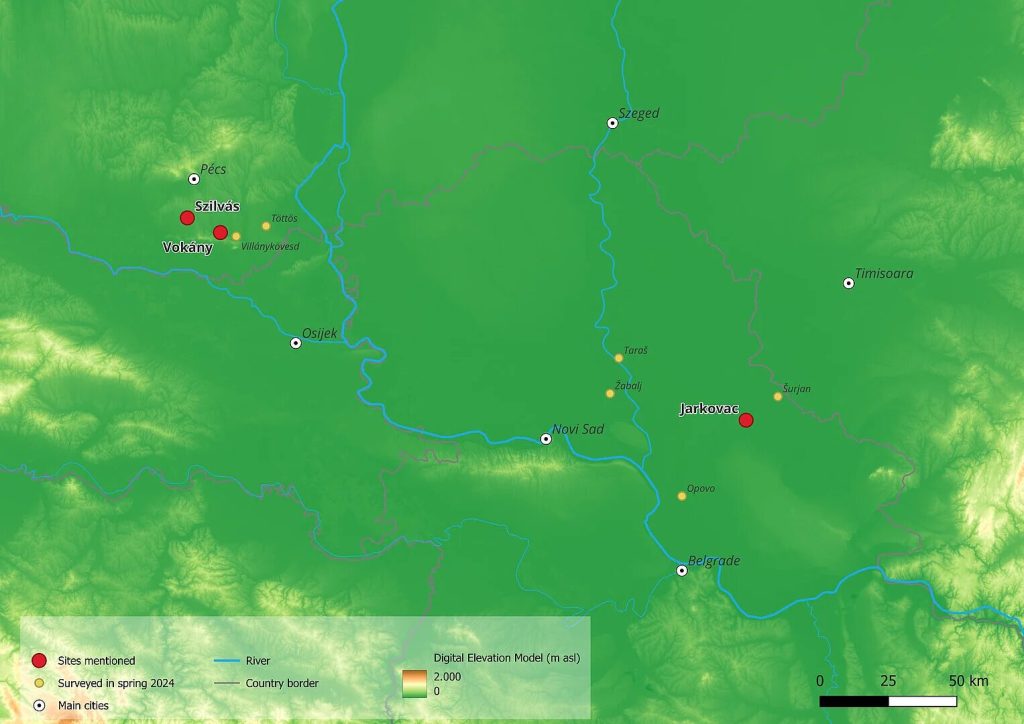

The ROOTS team discovered a previously unknown Late Neolithic settlement near the Tamiš River in Northeast Serbia.

The discovery provides important new insights into the Late Neolithic period in Southeast Europe.

The ROOTS team was formed in collaboration with the Museum of Vojvodina in Novi Sad (Serbia), the National Museum Zrenjanin and the National Museum Pančevo.

“This discovery is of exceptional importance as almost no large Late Neolithic sites are known in the Serbian Banat region,” says team leader Professor Dr. Martin Furholt from the Institute for Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology at Kiel University.

The newly discovered settlement is located near the modern village of Jarkovac in the province of Vojvodina.

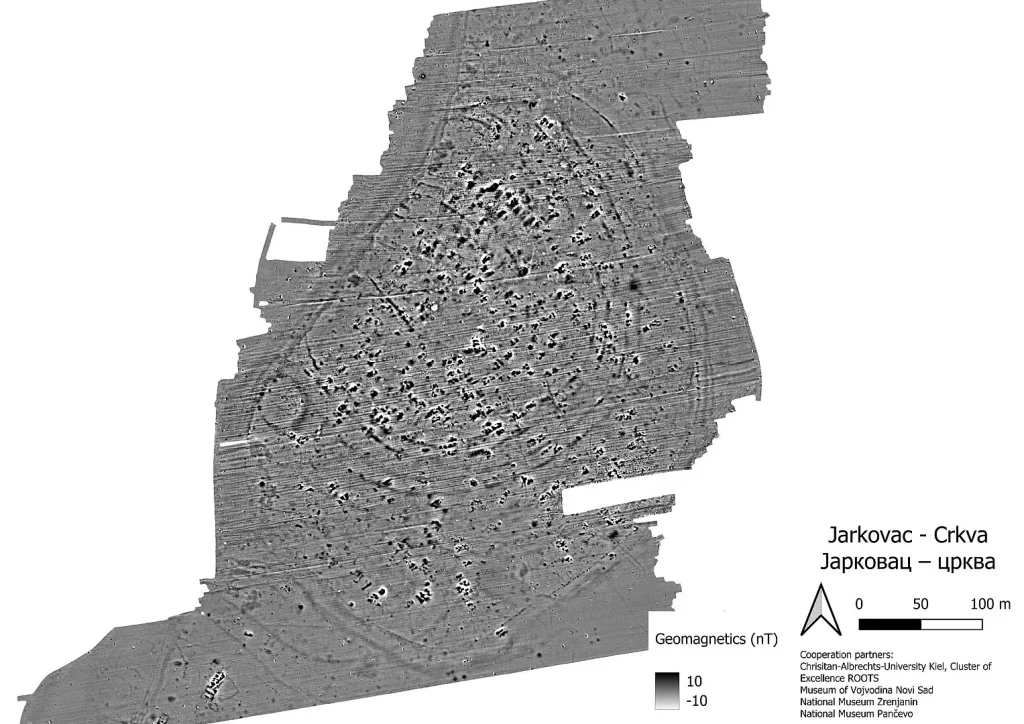

The settlement, mapped with the help of geophysical methods, covers an area of 11 to 13 hectares and is surrounded by four to six ditches.

“A settlement of this size is spectacular. The geophysical data gives us a clear idea of the structure of the site 7000 years ago,” says Fynn Wilkes, ROOTS PhD student and joint team leader.

In parallel with the geophysical surveys, the German-Serbian research team also systematically surveyed the surfaces of the surrounding area for artifacts. This surface material indicates that the site represents an occupation site of the Vinča culture, dating between 5400 and 4400 BC.

However, there are also strong influences of the regional Banat culture. “This is also remarkable because only a few sites containing material from the Banat culture are currently known in Serbia,” explains Fynn Wilkes.

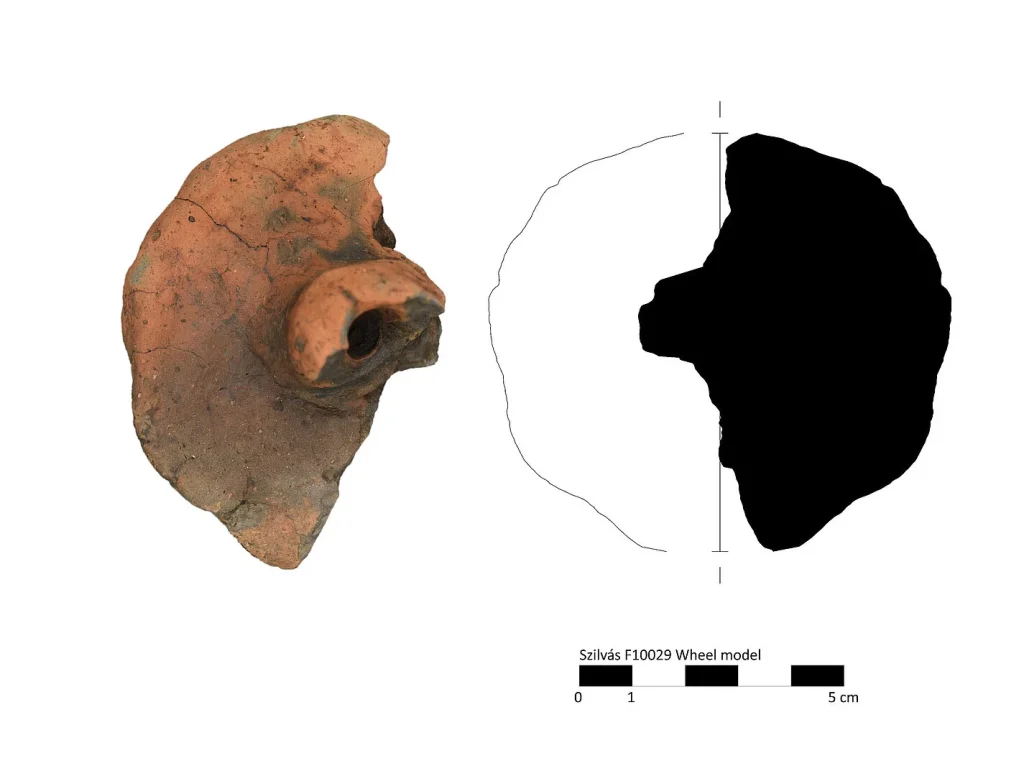

During the same two-week research campaign, the team from the Cluster of Excellence, together with partners from the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs, also investigated several Late Neolithic circular features in Hungary. These so-called “washers” are attributed to the Lengyel culture (5000/4900-4500/4400 BC). The researchers also used both geophysical technologies and systematic walking surveys of the surrounding area.

Thanks to the combination of both methods, the researchers were able to distinguish the periods represented at individual sites more clearly than before. “This allowed us to re-evaluate some already known sites in Hungary. For example, sites previously classified as Late Neolithic circular ditches turned out to be much younger structures,” explains co-team leader Kata Furholt from the Institute for Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology at Kiel University.

Highlights of the short but intensive fieldwork in Hungary included the re-evaluation of a Late Neolithic site previously dated to the Late Copper Age and Early Bronze Age Vučedol culture (3000/2900-2500/2400 BC) and the complete documentation of a Late Neolithic circular ditch in the village of Vokány.

“Southeastern Europe is a crucial region for answering the question of how knowledge and technologies spread in early human history and how this relates to social inequalities. This is where new technologies and knowledge, such as metalworking, first appeared in Europe. With newly discovered and reclassified sites, we are collecting important data for a better understanding of social inequality and knowledge transfer,” summarizes Professor Martin Furholt.

The results are being incorporated into the interdisciplinary project “Wealth and Knowledge Inequality” of the Cluster of Excellence ROOTS, which focuses on these issues. Analyses are still ongoing.

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply