Archaeologists discovered a Neolithic henge while searching for a nobleman’s grave in England

When archaeologists from Newcastle University were working to find the tomb of Saint Guthlac, who died in Crowland, Lincolnshire in 714 and became famous for his life of solitude, renouncing a life of wealth as the son of a nobleman, they surprisingly found a much more complex and ancient history than they expected.

Guthlac was found intact 12 months after his death. Upon this miraculous event he was venerated by a small monastic community. Guthlac’s popularity was a key factor in the founding of Crowland Abbey in the 10th century.

Early historical sources on Guthlac’s life are available mainly through the Vita Sancti Guthlaci (Life of St. Guthlac), written by a monk named Felix shortly after his death.

Archaeologists have tried to locate Guthlac’s tomb over the years, although there is little evidence of his life.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Anchor Church Field was considered the most likely site for the burial site. However, the lack of excavations and the increasing impact of agricultural activities in the area have prevented a comprehensive understanding of the site.

The team, including experts from the University of Sheffield, excavated Anchor Church Field and surprisingly found a much more complex and ancient history than they expected.

Their first discovery was a previously unknown Late Neolithic or early Bronze Age henge, a type of circular earthwork and one of the largest ever discovered in eastern England.

A henge is a prehistoric circular or oval earthen enclosure, dating from around 3000 BC to 2000 BC, during the Neolithic (also known as the new Stone Age) and early Bronze Age.

There are fewer than 100 henge still surviving in Britain and Ireland.

Because of its size and location, the henge would provide an important site for ceremonial activities in the area. At this time, Crowland would have been a peninsula surrounded on three sides by water and marshes, and the henge was located on a prominent and highly visible point jutting out into the Fens.

Even though the henge seems to have been abandoned over the centuries, but by the medieval period its fertile soil meant that it was probably regarded by monks like Guthlac as a unique landscape with a long and sacred history.

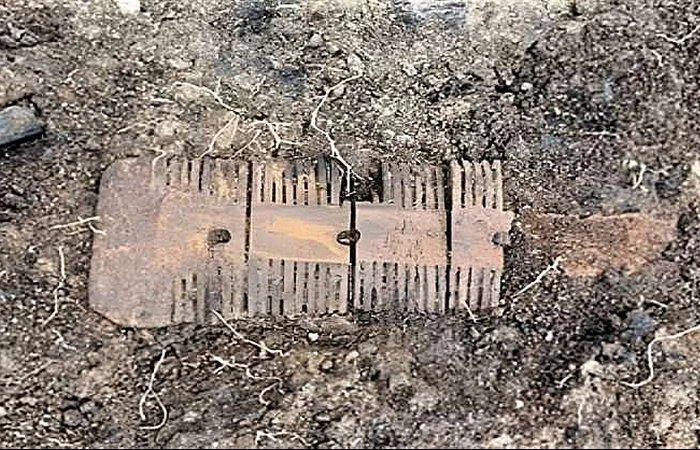

During Guthlac’s lifetime the henge was re-occupied and the excavation found large quantities of material, including pottery, two bone combs and glass fragments from a high-status drinking vessel. Frustratingly for the excavation team, all the structures of this date appear to have been destroyed by later activity, and these artifacts provide only a tantalizing glimpse of how the henge was used in the Anglo-Saxon period.

“We know that many prehistoric monuments were reused by the Anglo-Saxons, but to find a henge—especially one that was previously unknown—occupied in this way is really quite rare,” said Dr Duncan Wright, Lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at Newcastle University.

“Although the Anglo-Saxon objects we found cannot be linked with Guthlac with any certainty, the use of the site around this time and later in the medieval period adds weight to the idea that Crowland was a sacred space at different times over millennia.”

By far the most prominent features found during the excavations were the remains of a 12th-century hall and chapel, built by the Abbots of Crowland probably to venerate the hermits here. The hall would have been used for elite accommodation, perhaps for high-status pilgrims who were visiting Crowland. Although most of the stone from these buildings was robbed in the 19th century, documents suggest that the chapel on the site was dedicated to St Pega, Guthlac’s sister, who was herself an important hermit in the region. These same sources describe the chapel as lying in ruins by the 15th century, and it is possible that the site began to lose popularity as interest in pilgrimage waned around the Reformation.

“By examining the archaeological evidence we uncovered and looking at historic texts, it’s clear that even in later years Anchor Church Field continued to be seen as a special place worthy of veneration,” said Dr Hugh Willmott from the University of Sheffield. “Guthlac and Pega were very important figures in the early Christian history of England, so it is hugely exciting that we’ve been able to determine the chronology of what is clearly a historically significant site.”

Cover Photo: The Anchor Church Field project

Source: Newcastle University

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply