Archaeologists have discovered evidence that Neolithic farmers at the Anciens Arsenaux site in Sion, Switzerland, used animals to pull plows between 5,100 and 4,700 years ago.

This discovery is about 1,000 years older than the earliest known traces of plows and provides new insights into the beginnings of agricultural animal use in Europe.

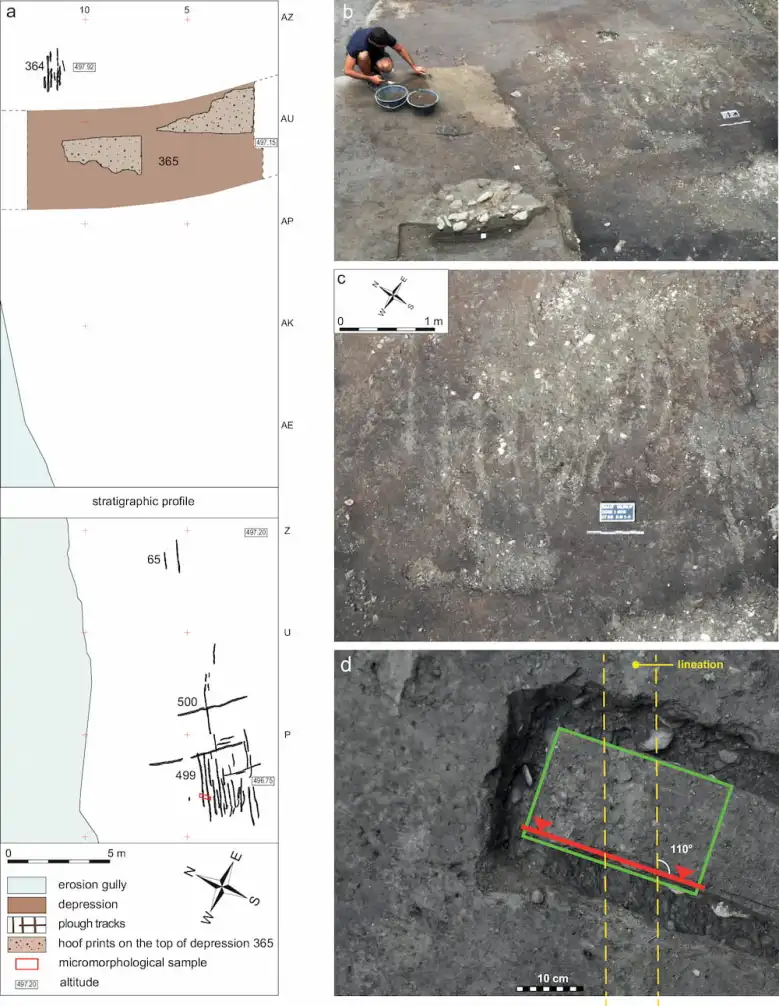

According to the report in Arkeonews; The presence of these alluvial deposits was undoubtedly the most important factor that made the discovery possible. Their discovery is extremely rare, as old plow marks are easily erased by erosion or subsequent agriculture. The only reason for the survival of the furrows at Sion is that the sediments of the surrounding stream quickly covered them, preserving the impressions of the furrows in the soil layers.

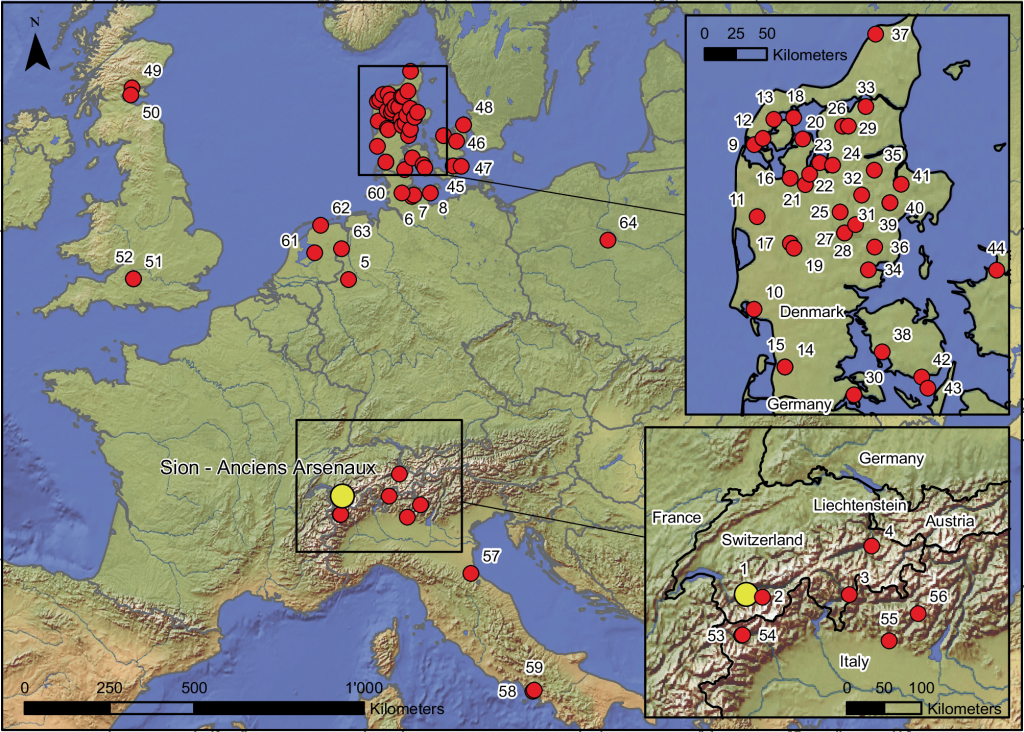

The strongest evidence of animals pulling plow-like tools in European agriculture before this discovery came from sites in northern Germany and Denmark, dating back some 3,700 years.

The Sion site contains consistent parallel grooves and marks in the soil, as if made by a plow being dragged along, as well as hoof prints, indicating that the pulling force came from domesticated cattle or oxen.

In the past, there was evidence from animal bones that people in regions such as Anatolia and the Balkans had used cattle or oxen for traction on and off since the seventh millennium BC. But this is the first concrete evidence of widespread plow agriculture found in prehistoric archaeology.

By performing detailed radiocarbon dating on the organic material found above and below these soil disturbances, the researchers were able to date this evidence firmly to the early Neolithic period.

These new findings suggest that animal traction in agriculture emerged well before agriculture emerged in the mountain region of Europe, the researchers say. It was not a later adaptation, but was probably an integral part of the early processes of continent-wide neolithization.

Compared to agriculture that relied solely on human labor and hand tools, the use of animal power to pull plows represents an important technological innovation that increased agricultural productivity and surplus and enabled the cultivation of much larger areas. In many early agricultural societies, economic stratification and social complexity are thought to have resulted from this overproduction.

The dating of the plough traces at Sion suggests that we need to reassess long-standing theories about the pace of agricultural intensification and its impact on society during the expansion of agriculture in Neolithic Europe, the study authors said.

The ability to work over larger areas with animal traction may have emerged from the very beginning, rather than being a later revolutionary development.

The site’s location in an important mountain valley may have been an ideal setting to quickly adopt and preserve evidence of plow use, the researchers note. Any early analog traces in the vast European plains, where Neolithic agriculture was first established, may have been erased by increasing erosion and subsequent intensive agricultural development.

For this reason, the archaeology team plans additional excavations in similar mountain environments in Switzerland and Italy to continue investigating the origins of animal traction in agriculture.

The research was published in Nature.