Scientists have discovered the smallest previously unknown monkey species in a clay quarry

An international research team has discovered the smallest previously unknown species of monkey during excavations in a clay quarry in Allgäu.

The monkey was named Buronius manfredschmidi.

Buronius manfredschmidi was found in the immediate vicinity of the great ape Danuvius guggenmosi “Udo” previously found in the same clay quarry. Danuvius was recorded as a species of ape that switched to upright walking about 12 million years ago.

Professor Madelaine Böhme and her team from the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment at the University of Tübingen, along with Professor David Began from the University of Toronto (Canada) and other scientists, published the findings of the study in the journal PlosOne on June 7.

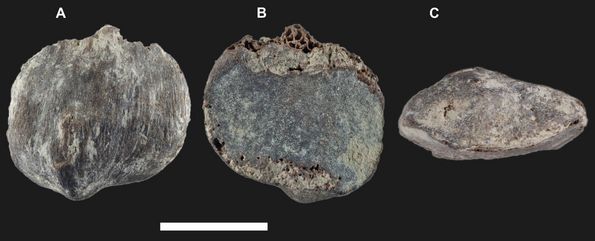

“The depositional conditions allow the conclusion that both great apes colonized the same ecosystem at the same time,” said Thomas Lechner, a member of the study team and the excavation director, who examined the fossils of two teeth and a kneecap belonging to Buronius.

The size of the fossils suggests that Burunius weighed only 10 kilograms. He was therefore significantly smaller than all living apes, ranging from 30 kilograms (bonobo) to 200 kilograms (gorilla), and also smaller than Danuvius, which weighed between 15 and 46 kilograms. Buronius’ body weight is comparable to siamangs, relatives of monkeys from Southeast Asia.

“Buronius’ kneecap is thicker and asymmetrical than Danuvius’,” Böhme adds. This can be explained by differences in the thigh muscles. Buronius may have been better adapted to climbing trees.

The tooth enamel of both great apes provided insight into their lifestyles. In primates, the thickness of tooth enamel is closely linked to their diet. Very thin enamel, for example in gorillas, indicates a vegetarian diet rich in fiber. A thick tooth enamel, as in humans, is indicative of an omnivore with a diet of hard and tough foods and high bite forces.

“Buronius’ enamel thickness is lower than that of other great apes in Europe and comparable to gorillas. On the other hand, the tooth enamel of Danuvius is thicker than that of any extinct species and almost reaches the strength of human tooth enamel,” says Böhme. The different enamel thickness corresponds to the shape of the chewing surfaces. The enamel is smoother in Buronius and has stronger cutting edges; that of Danuvius is notched and has blunt tooth ridges. “This suggests that Buronius was a leaf eater and Danuvius was an omnivore.”

If two species live in the same habitat (so-called syntopia), they need to resort to different resources to avoid competition. The context in which the Hammerschmiede fossils were found proves syntopia in monkeys for the first time in Europe. Bourunius, which ate small leaves, may have stayed longer in treetops and branches, the authors say. On the other hand, Danuvius, which was more than twice as large and capable of bipedalism, probably roamed over a wider area to find more diverse food sources. This can be compared to today’s syntopia of monkeys and orangutans in Borneo and Sumatra: Orangutans roam in search of food, while small fruit-eating monkeys stay in the treetops.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301002

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply