The oldest evidence of piercing was found in 11,000-year-old skeletons at Boncuklu Tarla

Archaeologists have found the earliest evidence of piercings in skeletons dating back 11,000 years at the Boncuklu Tarla excavation site.

The evidence will provide new insights into the body modification practices of early sedentary communities in Southwest Asia.

Beaded Field is located in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. There are settlement layers from the Late Epipaleolithic to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period.

Boncuklu Tarla was discovered in 2008 during the archaeological survey conducted prior to the construction of the Mardin/Dargeçit Ilisu Dam.

Analysis of the skeletons revealed that piercings were only practiced by adults. This suggests that the prehistoric tradition may have been a ritual associated with the coming of age ritual.

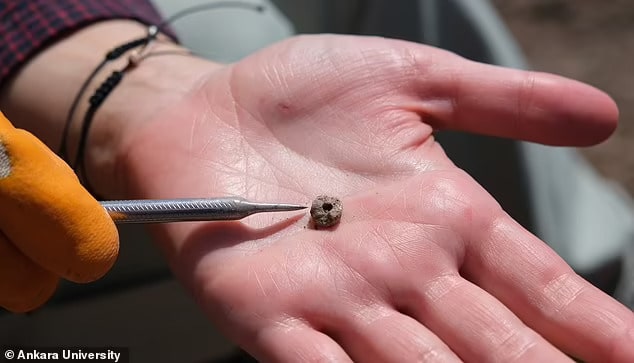

More than 100 ornaments buried next to 11,000-year-old skeletons at Beaded Tarla have been unearthed.

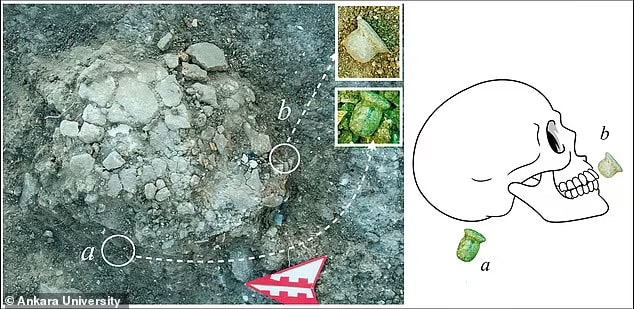

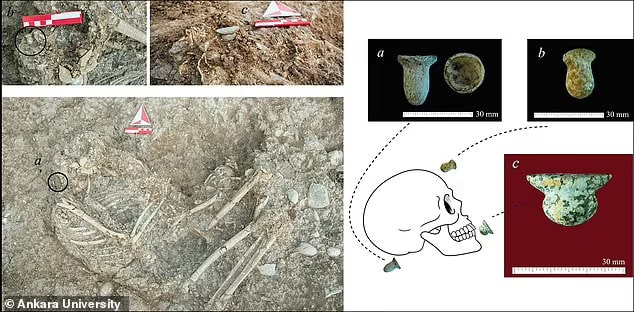

Made from materials such as limestone, obsidian and copper, these ornaments were found placed near the ears and jaws. The variety suggests that they were used for both ear piercings and a type of lower lip piercing called a labret. This theory is supported by wear patterns on the teeth of the skeletons similar to those observed in cultures known for labret use in the past and present.

Interestingly, the analysis revealed that the piercings were specific to adults, found in both men and women, but not in children’s graves. This suggests that piercings had a deeper meaning beyond aesthetics. The researchers suggest that they may have served as a rite of passage, marking the transition to adulthood.

Associate Professor Emma Louise Baysal, an expert on Neolithic personal adornment, emphasizes the significance of the find: “These ornaments, discovered in situ, provide the earliest contextual evidence for body modification practices in Southwest Asia. They challenge previous assumptions that date the beginning of such practices to around 7,000 BC.”

This discovery sheds light on the possible reasons behind early piercings. Labrets and ear ornaments were common in Southwest Asia during the early Neolithic, but not in the Neolithic regions of Central Anatolia.

The Boncuklu Tarla team believes this discovery will help clarify the terminology surrounding these artifacts and pave the way for a reassessment of existing Southwest Asian Neolithic data.

“It shows that the traditions that are still part of our lives today were already being developed during the crucial transitional period when people first began to settle in permanent villages in West Asia more than 10,000 years ago,” says Dr. Baysal.

Dr. Baysal concludes: “There were very complex ornamental practices involving beads, bracelets and pendants, including a very sophisticated symbolic world, all expressed through the human body.”

By continuing excavations at Boncuklu Tarla, the researchers hope to learn more about the choice of raw materials and the links between general decorative activities and bodily ornamentation traditions.

The findings were published in the journal Antiquity.

https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.28

Cover Image: Illustration of the hypothetical use of labrets and ear ornaments found at Boncuklu Tarla. Credit: Ergül Kodaş, Emma L Baysal et al. / Antiquity

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply