Who will solve the puzzle of the Bronze Age tin?

The origin of the tin used to make Bronze Age swords, helmets, bracelets, plates, and pitchers has been a topic of discussion among experts for 150 years.

Discovering the sources of tin can provide extensive insights into early trade relations between Central Asia, Mesopotamia, North Africa, the Levant, and Europe, and thus shed light on the early globalization that reshaped the world.

The key to solving this puzzle may lie in the cargo of a trade ship that sank near Uluburun on the western coast of Türkiye around 1320 BC. The shipwreck was discovered by divers in 1982, and its cargo was salvaged by underwater archaeologists. In addition to luxury items, it contained 10 tons of copper ingots and one ton of tin ingots, which was much more than previously found from the Bronze Age.

Ernst Pernicka, a senior professor at the University of Tübingen and the scientific director of the Curt Engelhorn Center for Archaeometry (CEZA), said, “Even 40 years after the discovery of Uluburun, the puzzle still persists, but we are getting closer to solving it by applying new methods.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

In a recent study published in the Frontiers in Earth Science journal, CEZA researcher Dr. Daniel Berger and co-authors, including Pernicka, contradicted a research team led by Professor Wayne Powell of Brooklyn College in New York, who claimed to have conclusively determined the origin of the tin from the Uluburun wreck in a November 2022 article in Science Advances.

Powell’s team claimed that the majority of the tin came from the Muhiston tin deposit in northwest Tajikistan and two mines near the Türkiye-Syria border in the Toros Mountains. They took 105 tin ingot samples from the wreck and determined the chemical and isotopic fingerprints of 90% of them. They specifically measured the isotopic ratios of tin and lead, which provide clues about the origin of tin, similar to its chemical composition. Additionally, the trace element tellurium ratio pointed to tin deposits in Central Asia. Powell’s team claimed that based on matching signatures between the ingots from Uluburun and tin ore samples from the mentioned mines, they could make a clear association.

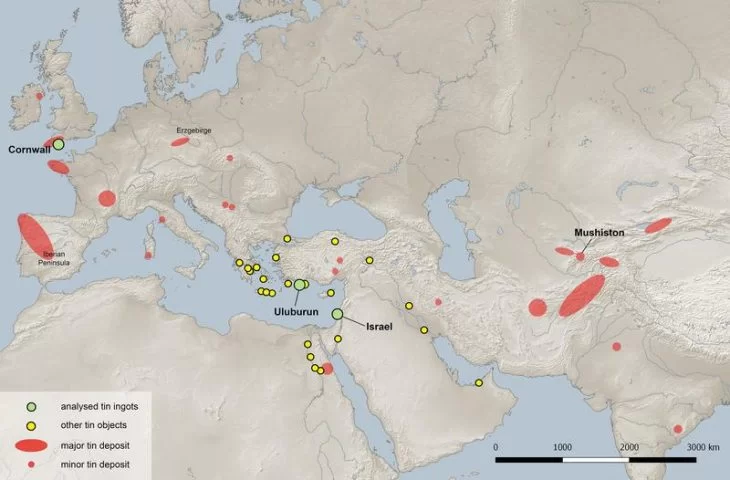

However, Berger and his co-authors stated, “The data do not support this interpretation; they do not allow for a conclusive conclusion.” For the current study, Berger thoroughly reviewed the chemical and isotopic analyses obtained from previous studies and cross-checked them with Powell’s data set. “Due to isotopic ratios and chemical properties, the possibility that at least some of the tin ingot cargo from the Uluburun wreck came from Cornwall in England is even higher. This is particularly indicated when compared to Bronze Age tin ingots from England and Israel, which we have previously examined over a similar provenance issue. However, it is also possible that the tin came from the Saxon-Bohemian Erzgebirge or the Iberian Peninsula,” said Berger.

The Bronze Age, in general, lasted from the end of the fourth millennium BC to the beginning of the first millennium BC, but it had different start and end dates depending on the region of the world. Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin in a ratio of nine to one, is significantly harder than copper alone. Copper ores can be found in many regions of Eurasia and Africa. However, tin ores available during the Bronze Age were only found in a few places in Central Asia, Iran, and Europe. It’s even more surprising that some of the oldest bronze artifacts have been found in the city-states of Mesopotamia in the Tigris-Euphrates river system, where there was no tin deposit; tin had to be obtained through long-distance trade routes.

Pernicka and Berger state, “Numerous archaeological finds suggest that during the Bronze Age, the British Isles and Central Europe formed an economic sphere with the Mediterranean region, and the transportation routes of the Danube, Rhine, and Rhône rivers were connected through trade or ocean routes.” For example, the presence of amber beads traded from the Baltic in the Uluburun shipwreck indicates the existence of north-south trade routes.

The use of standardized weights had spread from Egypt and Mesopotamia through Syria, Anatolia, and the Aegean to Central Europe by the second millennium BC. These standardized weights were used to measure products, including tin ingots. During the time of the Uluburun shipwreck, neither weight systems nor documented trade connections with Central Asia for the Middle East, Europe, and the Eastern Mediterranean can be established. This emphasizes the likelihood that tin came from the west.

Cover Photo: Untouched tin ingot. Institute of Nautical Archaeology

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply