A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

A new study has been published on the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European languages, spoken by half of the world’s population today.

Indo-European language was spoken in Anatolia during the Bronze Age and Iron Age periods by the Hittites, Luwians, Lycians, and Phrygians.

The analysis results of the study titled “A New Hybrid Hypothesis for the Origin of the Indo-European Languages,” conducted by the Max Planck Institute, indicate that the Indo-European language family is approximately 8100 years old and that its five main branches separated around 7000 years ago.

The study has been published in the Science journal.

The study shows that the Indo-European language family is approximately 8100 years old.

For the past 200 years, debates about the origin and spread of the Indo-European languages have been ongoing. These debates have led to the emergence of two main hypotheses.

One of these hypotheses suggests a ‘Steppe’ origin, proposing that approximately 6000 years ago, the Pontic-Caspian Steppe was the homeland of the Indo-European languages. The other hypothesis, known as the ‘Anatolian’ or ‘Farming’ hypothesis, suggests an even older origin, approximately 9000 years ago, tied to early agriculture in Anatolia.

These two hypotheses have been at the center of discussions and research on the subject of the Indo-European language family’s origins and dispersal.

The contradictory results about the age of the Indo-European language family have arisen from previous phylogenetic analyses due to errors and inconsistencies in the datasets used, limitations in the analysis of ancient languages, and the methodologies employed.

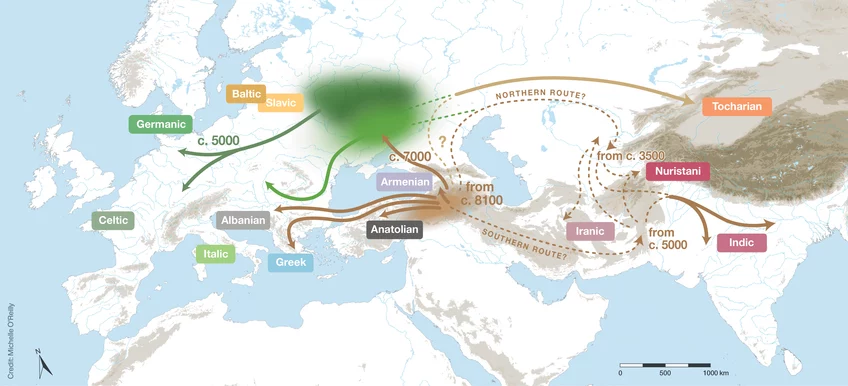

A hybrid hypothesis for the origin and spread of the Indo-European languages. The language family began to diverge from around 8100 years ago, out of a homeland immediately south of the Caucasus. One migration reached the Pontic-Caspian and Forest Steppe around 7000 years ago, and from there subsequent migrations spread into parts of Europe around 5000 years ago. © P. Heggarty et al., Science (2023)

To address these discrepancies, researchers from the Linguistic and Cultural Evolution Department at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology formed an international team comprising more than 52 language experts.

They created a new foundational wordlist dataset from 161 Indo-European languages, which included 80 ancient or historical languages.

This more comprehensive and balanced sampling, combined with rigorous protocols for coding lexical data, resolved the issues present in the datasets used in previous studies.

In their research, the team utilized Bayesian phylogenetic analysis.

Russell Gray, the Head of the Linguistic and Cultural Evolution Department and the senior author of the study, emphasized that they took utmost care to ensure the robustness of their inferences. He stated, “Our chronology is robust among a wide range of alternative phylogenetic models and sensitivity analyses.”

Through these analyses, the researchers estimated that the Indo-European language family is approximately 8100 years old, and its five main branches separated around 7000 years ago.

The Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family is not derived from the steppe.

The first author of the study, Paul Heggarty, stated that recent ancient DNA data shows that the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family did not originate from the steppe but rather emerged from within or in close proximity to the northern reaches of the Fertile Crescent. This region is considered the oldest source of the Indo-European family. The linguistic tree topology and the divergence dates also indicate that other early branches might have spread directly from there, rather than through the steppe.

As a result, the authors of the study proposed a new hybrid hypothesis for the origin of the Indo-European languages. According to this hypothesis, there was a primary homeland in the south of the Caucasus, and then, some branches of the Indo-European languages moved northward towards the steppe, eventually entering Europe through expansions associated with the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures.

Russell Gray stated, “Ancient DNA and linguistic phylogenetics converge to suggest that the resolution of the 200-year-old Indo-European mystery lies in a hybrid of the farming and steppe hypotheses.”

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply