A Remarkable Newly Deciphered Hittite Tablet Sheds New Light on The Trojan War

The Hittites, creators of invaluable written records from the Anatolian Bronze Age, have gifted us thousands of cuneiform tablets unearthed at sites like their capital, Hattusa (modern Boğazköy, Çorum). Hittitologists, by deciphering these tablets, have revealed crucial insights into Hittite history, religion, and economy, while also providing a window into life in ancient Anatolia.

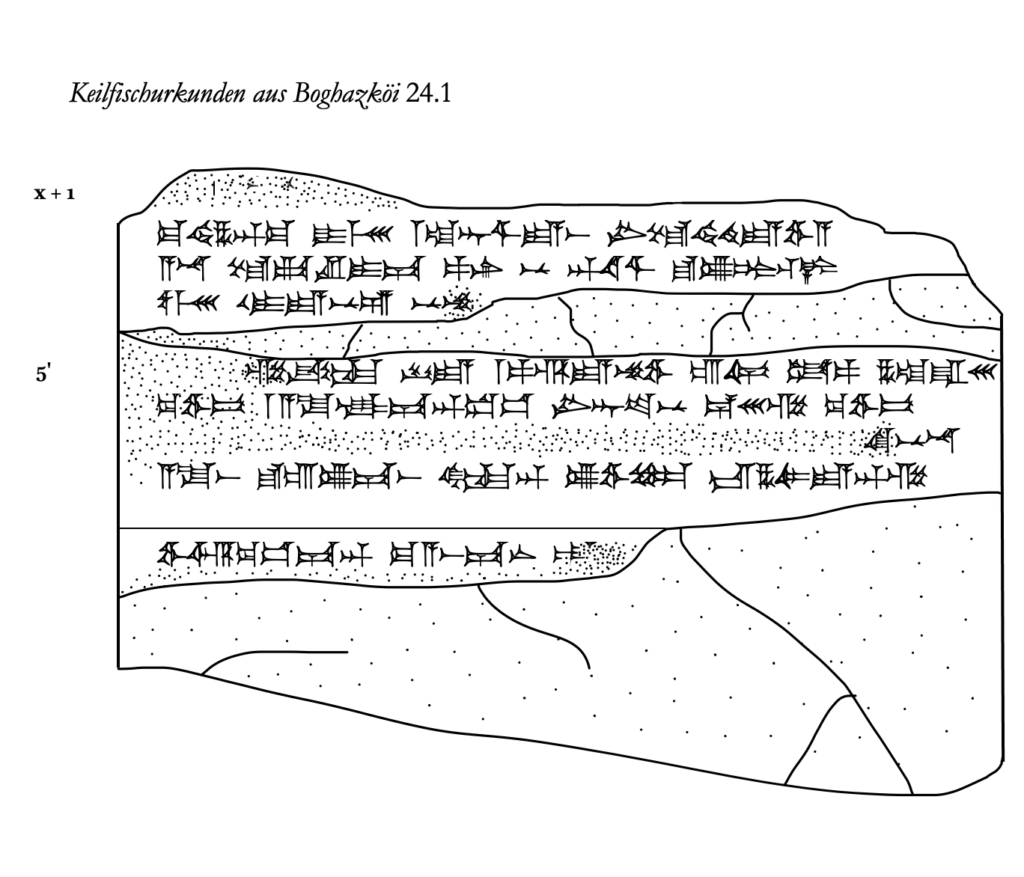

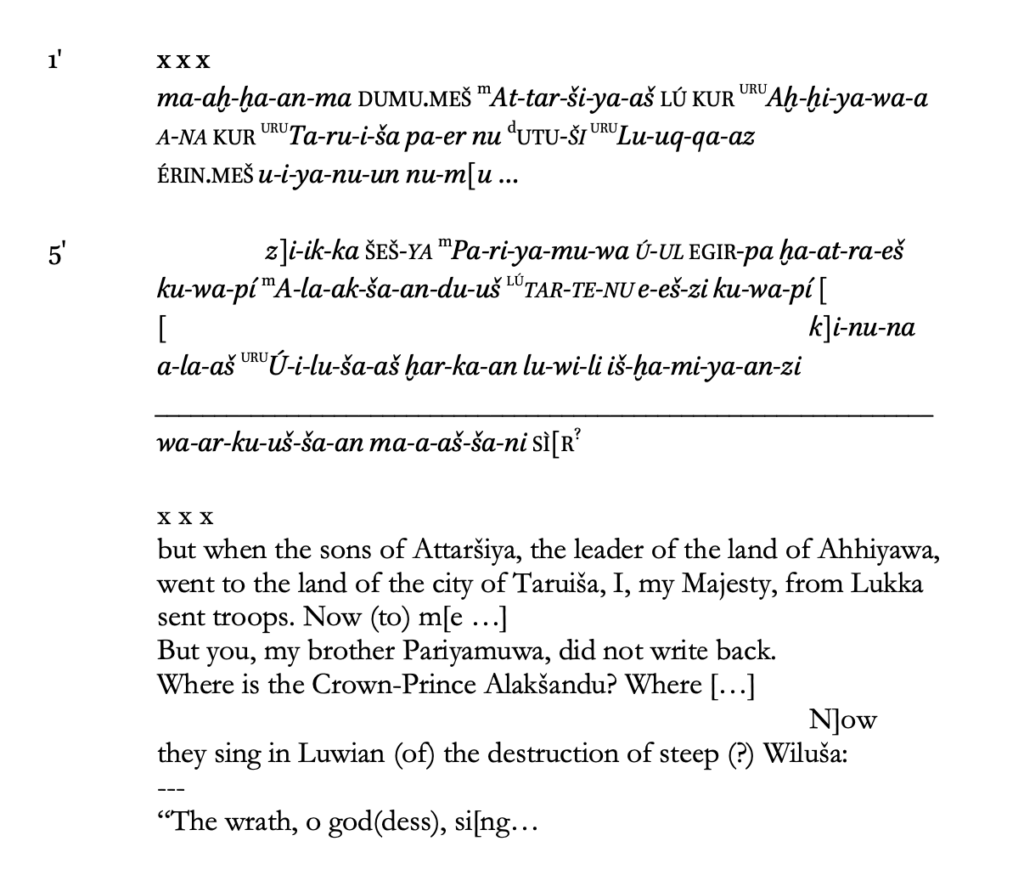

A recent discovery, a tablet from this vast Hittite archive, offers extraordinary information about the Trojan War, a pivotal event in the Anatolian Bronze Age. Deciphered under the direction of Michele Bianconi of Oxford University and recently published as “Keilfischurkunden aus Boghazköi 24.1,” this tablet presents one of the most compelling written links between Bronze Age Anatolia and the epic tradition culminating in Homer’s Iliad.

While previous Hittite records referenced familiar names such as Wiluša (Troy/Ilion), Ahhiyawa (the Achaeans), and figures like Alaksandu and Attaršiya (possibly Atreus or an early Achaean leader), this new tablet goes further. It not only reinforces the geopolitical dynamics of the Late Bronze Age but also offers an unprecedented literary fragment, hinting at a local Luwian poetic tradition about the fall of Troy, predating Homer by centuries.

Key Findings from the Hittite Text

The tablet details royal correspondence between a Hittite ruler and an individual named Pariyamuwa, likely a regional king or vassal. It recounts Attaršiya of Ahhiyawa and his sons attacking Taruiša (Troy). This narrative aligns with CTH 147 (“The Indictment of Madduwatta“), which portrays Attaršiya as a powerful Achaean figure aggressively operating in Western Anatolia.

However, the most striking element is a Luwian poetic fragment at the tablet’s end, seemingly narrating the fall of Wiluša (Troy). This rhythmic verse, “In Luwian they speak of the destruction of steep (?) Wiluša: ‘Rage, goddess, sing…’,” bears an uncanny resemblance to the famous opening of Homer’s Iliad: “Sing, goddess, the anger of Achilles…”

Previously, scholars of Aegean prehistory and oral tradition had to rely heavily on conjecture when linking Hittite archives to Homer’s poems. While political evidence existed for a city named Wiluša (Troy) and the understanding that Ahhiyawa represented a western power with a Greek-speaking elite, a literary or semi-literary bridge was missing.

According to Archaeologist, This tablet, for the first time, suggests the existence of a Luwian poetic corpus and a work narrating Troy’s fall. Though fragmentary, the passage indicates a rhythm likely intended for oral performance. The dactylic or spondaic structure, echoing Homer’s hexameter, may point to a broader epic tradition in Anatolian courts, predating the Iliad’s composition in the 8th century BC.

References to divine wrath and destruction further suggest thematic and formal parallels with the Greek epic tradition. Given that Troy was an Anatolian city and the region hosted a bilingual (or multilingual) population, including Hittites, Luwians, and other Indo-European groups, the existence of a local narrative tradition about Troy’s fall is both plausible and now tentatively evidenced.

The Issue of Prehistoric Texts and the Trojan War

This discovery reignites a crucial academic debate: Did Bronze Age Anatolia possess its own narrative tradition about Troy’s fall, separate from or ancestral to Homer’s poem?

Until now, no long-form poetic texts related to the Trojan War had been found from the Late Bronze Age. While Mycenaeans left Linear B tablets, these were purely administrative and lacked mythological content. The Hittites, on the other hand, maintained a rich archive of myths, treaties, and diplomatic correspondence, yet a definitive poetic narrative about Wiluša’s destruction was absent.

This new tablet changes the landscape. If these Luwian lines are indeed part of a larger epic or lament, it suggests that an oral tradition about Troy’s fall existed in Anatolia long before Homeric bards in Ionia. This tradition may have spread westward or been inherited by the Greek-speaking population on the coast, eventually evolving into the Iliad. Alternatively, the Iliad may be a Greek reworking of a shared Indo-European mythological repertoire, adapted to the political realities and cultural memories of Iron Age Greece.

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply