Hieroglyph meaning “city” in the Luwian language spoken in Anatolia deciphered

A research team led by Petra M. Goedegebuure of the University of Chicago has published a groundbreaking study in the academic journal Anatolian Studies on the Luwian language for ‘city’ spoken in ancient Anatolia.

In addition to providing a thorough linguistic analysis of the term in question, this study investigates the cultural and social meanings of cities in ancient Luwian records, giving researchers fresh perspectives on how cities and territorial organization functioned in ancient Anatolia.

For many centuries, Luwian, an Indo-European language belonging to the Anatolian group, dominated central and southern Anatolia. It was one of the primary linguistic families of this region, along with its sister language, Hittite. It survived the collapse of the Hittite Empire in the 12th century BCE and continued to be used in the small post-Hittite kingdoms until the Assyrian Empire overran them in the 7th century BCE.

The Luwian culture thrived in Bronze Age western Asia Minor. Linguists have primarily studied the Luwian people through documents from Hattuša, the Hittite capital in central Asia Minor. Although the recognition of the Luwian culture has been delayed, from a linguistic point of view the Luwian culture is relatively well known.

A thorough understanding of Luwian culture has been made possible by the more than 33,000 documents from Hattuša, the capital of the Hittite Kingdom.

There are roughly 300 inscriptions in the Luwian corpus written in Anatolian hieroglyphs. Even though this is big enough that most people understand Luwian, not every word is fully written down. The word for “city, town” is one of them. It is noteworthy that the term for such a fundamental idea is still unknown, given the significance of cities in Luwian monumental inscriptions.

The discovery of the Anatolian hieroglyph URBS, which has been deciphered in contexts that describe urban life, is among the research’s most remarkable findings. The Luwian word for “city” has no direct equivalents in other Anatolian languages, such as Hittite or Lycian, which contributes to the lack of agreement up to this point regarding the exact meaning of this logogram. Its exact interpretation has become difficult as a result.

According to Goedegebuure, who uses a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates iconographic, morphological, orthographic, and archaeological analysis, the word that the URBS hieroglyph represents may be allamminna/i- or allamminna, which means “fortified settlement.” In addition to being interpreted as “city,” this word emphasizes the significance of defense and fortification in the Luwian concept of urban life.

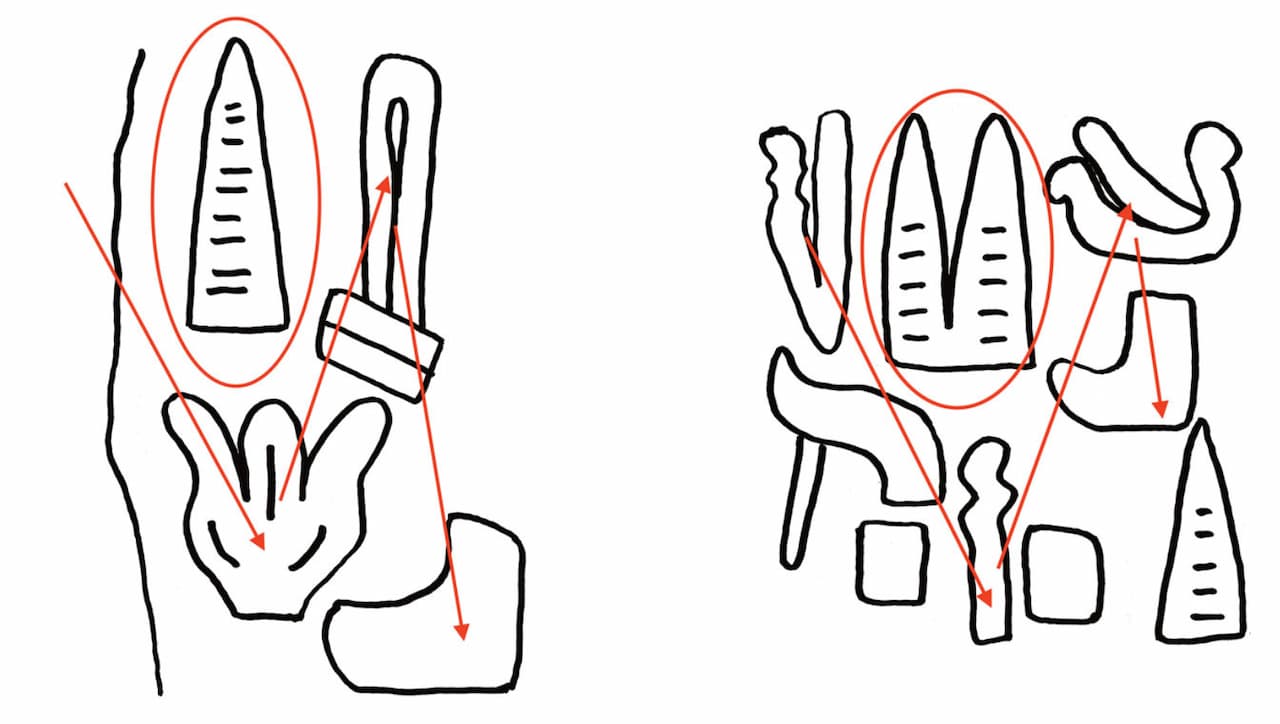

Goedegebuure examined the morphology of the inscriptions and the architectural characteristics of Anatolian cities from that time period in order to comprehend the intricacy of the term allamminna and its representation in hieroglyphics. The URBS logogram, according to the author, most likely depicts a merlon or battlement, an elevated portion of the wall’s fortification typical of defensive structures. This illustrates in a single symbol the intimate relationship between the Luwian concept of “city” and defensive structure. Thus, this hieroglyph not only symbolizes a city as an urban center but also as an entity strongly linked to its defensive structure.

Goedegebuure addressed the difficulties posed by the examination of Anatolian hieroglyphs in order to arrive at her conclusion about the Luwian word for “city.” Despite being frequently found in inscriptions, many words in the Luwian system are written using logograms that lack full phonetic representation, which is a peculiarity. For instance, the word for “house” is primarily DOMUS, and the word for “sheep” is OVIS, both of which lack phonetic signs. Similarly, it is challenging to accurately interpret the URBS symbol because it frequently appears without a complete syllabic transcription.

Despite being restricted to a few hundred inscriptions and seals, the Luwian corpus is comparatively large in comparison to other ancient Anatolian languages, according to the research, unlike the copious Hittite cuneiform documentation. In the last few decades, our understanding of Anatolian hieroglyphs has greatly expanded thanks to etymological research, contextual analysis, and comparisons of lexical combinations.

However, many hieroglyphs and words remain incompletely understood, like the term for “city”, which now seems to be resolved with Goedegebuure’s study.

Cover Image Credit: Hieroglyphic Luwian text, Ankara, Türkiye

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply