How did the non-seafaring Hittites of the Bronze Age maintain control over Eastern Mediterranean trade?

During the Bronze Age, Anatolia possessed significant overland trade routes. The trade colonies established by Assyrian merchants formed the main arteries of trade in the 2nd millennium BC. These Assyrian traders transported goods from Mesopotamia to the western reaches of Anatolia through trade routes, contributing to the development of commerce.

Notably, the Assyrian traders not only brought commercial vitality but also introduced writing to the region.

The development of overland trade routes during the Late Bronze Age gradually paved the way for extensive use of maritime trade.

The discovery of the Ulu Burun shipwreck, in particular, highlights that by the 2nd millennium BC, the Eastern Mediterranean had become a kind of hub for the ancient world and maritime trade was beginning to form the backbone of the international economy.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Dr. Eric Jean*, a faculty member at the Department of Protohistory and Near Eastern Archaeology at Hittite University, suggests that we might be curious about the role of the Hittites, one of the major powers of the time and the region, in their relationship with the sea in this context.

Jean stated, “The Hittites, settled in Central Anatolia, were not a maritime people, but their need for a navy can be understood not only from written sources but also from the data revealed through archaeological research.”

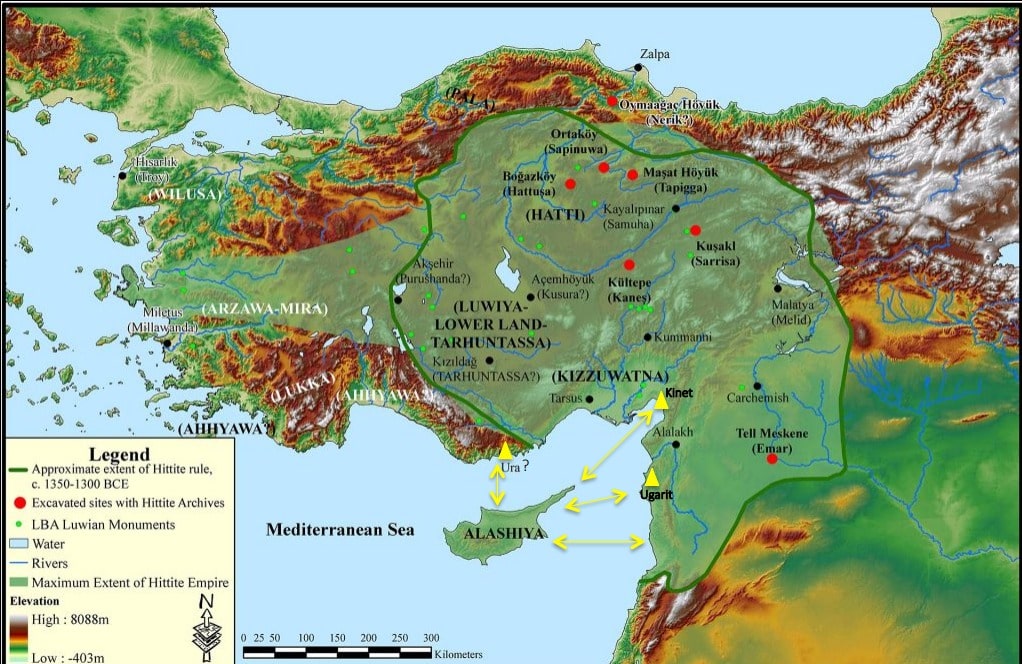

The texts reveal that the navy was supplied or organized by the Hittites’ Levantine allies (Amurru, Ugarit) or vassals. Along with geographical advantages, the interpretation of these texts demonstrates the significance of the distribution of goods imported from the Mediterranean to the Hittite centers in Central Anatolia, highlighting the importance of the Cilician coasts and ports in the trading process.

Were the Hittites a maritime empire?

The discovery of archaeological evidence indicating the Hittites’ reach to the island of Cyprus (Alashiya) and their trade relations with the island, as well as the importation of goods, especially from Egypt and the Levant region, to Ura (in the present-day Silifke district) raises the question: Were the Hittites a maritime empire?

Eric Jean notes, “If we listen to Gurney: ‘The Hittites had no fleet, and we do not know what sort of ships they used to reach Cyprus, which seems to have been under their control.'” However, as Özlem Sir Gavaz has also recognized, this situation leaves unanswered how domination was established over Alashiya. According to Sir Gavaz, “With the Hittite control of Northern Syria and the port cities therein, they not only gained influence over land and sea trade but also became owners of a capable navy.”

“As suggested by the sea cults that guaranteed the security of the kingdom’s maritime boundaries, control over the seas was necessary not only for ideological purposes of royalty and religion but also for economic development. This control was based on asserting dominion over the territories of subject kingdoms. While the Hittites were not a seafaring people, they led a well-organized empire that understood how to delegate authority and accommodate realities in the countries under their dominion, resulting in greater efficiency and centralized governance,” explained Jean.

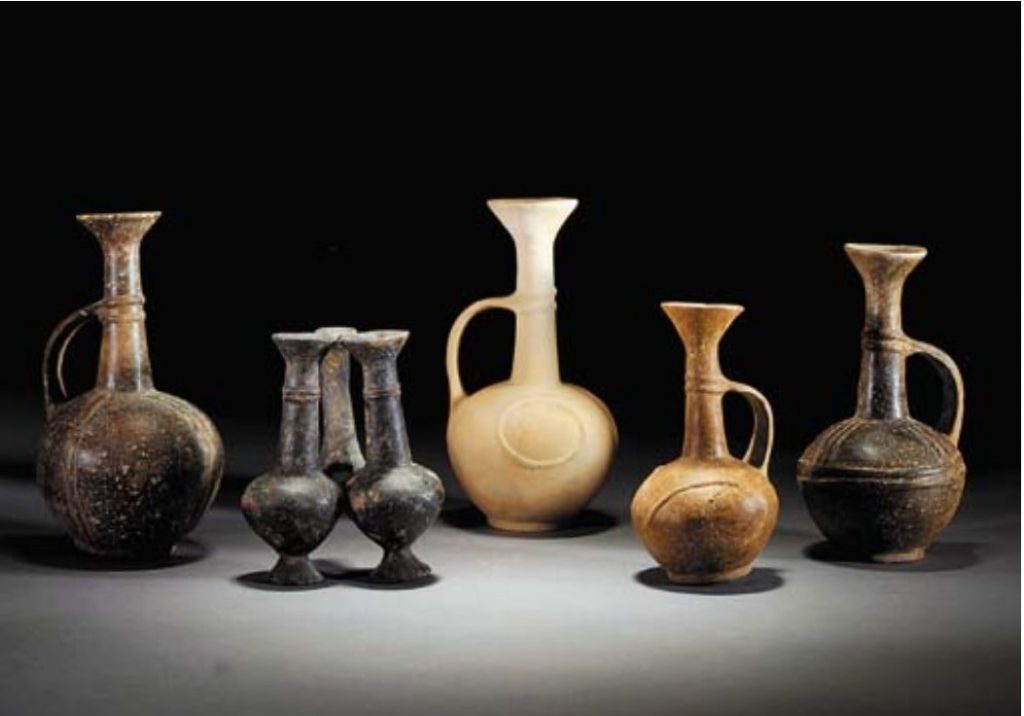

“We can also mention the Hittite navy, but it was a navy existing prior to the subjugation of northern Syria in the 14th century. The involvement of Kinet Höyük (Alexandretta) in Hittite affairs in the mid-16th century and the supply of red polished wheel-made vessels and blue-purple fabrics by at least the 15th century suggests that the initial Hittite navy might have been created from the fleets of Cilicia through allied Kizzuwatna or the Ura region. The likely production of polished wheel-made vessels in the region of the Taurus Mountains of Cilicia does not nullify the role of Ura in supplying the Hittites; perhaps the function of the Ura port was primarily for exporting this pottery.”

Ura might have played a leading role in the formation of the Hittite navy.

“Most maps depicting the international dimension of maritime trade in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age do not encompass the ports of Cilicia. However, I reiterate that, from I. Suppiluliuma to II. Suppiluliuma, before the use of Ugarit’s ports and navy, the Hittite kings were utilizing the ports of Cilicia. This absence perhaps reflects the paradoxical situation of the Hittite Empire: an imperial power yet relatively closed off when considering the rare goods imported to Central Anatolia. Indeed, the exception of the red polished wheel-made vessels signifies these select items.”

Furthermore, Chris Monroe suggests that some Ura merchants worked for the Hittite Kingdom, while others might have been employed by private individuals. As proposed by Stefano de Martino, Ura had more independence than previously thought; this autonomy or relative independence was likely not only political but also economic. In my view, if the fleets of the subjugated regions were put into service of the Hittite kingdom, maritime trade was partly based on private entrepreneurial activities that allowed Ura and Ugarit merchants to enrich themselves. According to the Ugarit document RS 17.130 from the 13th century, the way “His Majesty’s merchants,” meaning Ura’s merchants, looked after their comfort at the expense of Ugarit’s, might reflect the role Ura played in the formation of the Hittite navy.

* From Dr. Eric Jean’s lecture titled “A Navy of a Non-Seafaring People? The Hittites and Maritime Control,” presented within the scope of the “107th Anniversary of Hittitology” events organized by the Department of Hittitology at Istanbul University’s Faculty of Literature

Source arkeonews.com

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply