The discovery of a human-like monkey species in Çankırı is altering our understanding of the origins of humanoid species

Eight years ago, in the Çorakyerler Vertebrate Fossil Site in Çankırı, it was determined that the monkey bones found belonged to a different species, and a tailless monkey-like species with humanoid features was named “Anadoluvius turkae.”

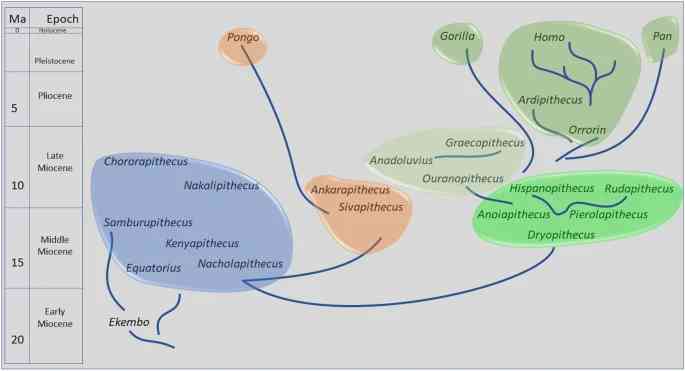

Anadoluvius turkae, estimated to have lived around 8.7 million years ago, supports the hypothesis that tailless and bipedal Anadoluvius species emerged in Europe and spread to Africa, among humanoid species.

The latest research on Anadoluvius turkae has been published in the journal Communications Biology.

The article co-authored by Professor David Begun from the University of Toronto and Professor Ayla Sevim Erol from Ankara University, published in the journal Communications Biology, presents information that challenges long-standing ideas about the origins of humanoid species.

According to the information provided in the article, the newly discovered tailless monkey fossil, estimated to be 8.7 million years old and found in Turkey, challenges the accepted notions regarding the origins of humanoid species. The Anadoluvius turkae fossil supports hypotheses suggesting that before African primates and the earliest humanoid species migrated to Africa around nine to seven million years ago, they emerged in Europe.

Radiation analysis of the tailless monkey known as Anadoluvius turkae reveals an extensive history of hominins in Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean.

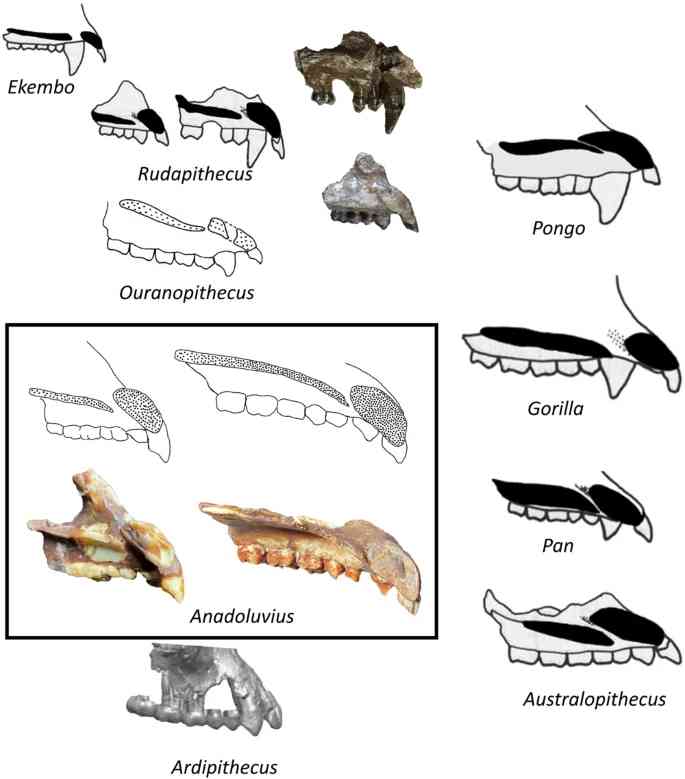

Professor David Begun states, “Our findings also indicate that hominins not only evolved in Western and Central Europe, but also likely spent over 5 million years evolving there and spreading to the Eastern Mediterranean before eventually dispersing to Africa, possibly as a result of changing environments and decreasing forests. Members of the species to which Anadoluvius turkae belongs have currently only been identified in Europe and Anatolia. The completeness of the fossil allowed us to perform a broader and more detailed analysis using numerous characters and features encoded in a program designed to calculate evolutionary relationships. After mirror imaging, the facial part mostly became whole. The forehead was also present, preserved up to the top of the skull. Previously described fossils did not have such a substantial portion of the skull.”

This information adds further context to the research and sheds light on the significance of the Anadoluvius turkae discovery.

Prof. Ayla Sevim Erol states, “Although we do not have limb bones, based on the examination of jaw and teeth, the neighboring animals, and geological indicators of the environment, it seems that Anadoluvius lived in relatively open conditions, unlike the forest environments where large primates lived. It resembles more the environments we associate with the first humans in Africa. Strong jaws and large, thick enamel teeth suggest a diet that included hard food items obtained from terrestrial sources such as roots and tubers.”

Ayla Sevim Erol says, “The formation of the modern African open savanna fauna in the Eastern Mediterranean has been known for a long time, and now we can also add African primates and human ancestors to the list of newcomers.”

According to the findings, Anadoluvius turkae is argued to be a branch of the evolutionary tree that includes chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and the first humanoid species that inhabited the shores.

While it’s currently assumed that modern African primates and the oldest known humanoid species originated solely in Africa, the authors of the article highlight that both their ancestors could potentially have come from Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, suggesting that these hypotheses might be more accurate.

The discovered species in Turkey, Anadoluvius, along with Ouranopithecus found in Greece and Graecopithecus found in Bulgaria, make up a group that is closest in anatomy and ecology to the known oldest hominins or humanoid species. The newly found fossils present the best-preserved examples of this early hominin group, providing the strongest evidence so far for the emergence of this group in Europe and its subsequent spread to Africa.

According to the information in the article, it is estimated that the Balkan and Anatolian monkeys evolved from species in Western and Central Europe.

The research, with more comprehensive data, provides evidence that these other species might also have been hominins, suggesting a higher likelihood of the entire group evolving and diversifying in Europe.

An alternative scenario proposed that different monkey species independently spread from Africa to Europe over several million years and then went extinct.

Begun states, “The second scenario is a favorite proposal among those who do not accept the European origin hypothesis, but there is no evidence for it. These findings contradict the long-held view that African primates and humans evolved exclusively in Africa. Remains of the first hominins are abundant in Europe and Anatolia, but there is no trace of hominin remains in Africa until about seven million years ago when the first hominins are thought to have emerged there.”

This new evidence supports the hypothesis that hominins emerged in Europe around nine to seven million years ago and spread to Africa along with various other mammals, but it doesn’t definitively prove it. Therefore, to establish a definite connection between the two groups, we need to discover more fossils from both Europe and Africa within the range of eight to seven million years old.

Source Sevim-Erol, A., Begun, D.R., Sözer, Ç.S. et al. (2023). A new ape from Türkiye and the radiation of late Miocene hominines. Commun Biol 6, 842.

Cover Photo by Mark Thiessen/National Geographic

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply