Uncovering Unknown Migrations: A Scandinavian Roman Gladiator in York Before the Viking Age

Scandinavian genetic markers were found in the British Isles several centuries earlier than previously believed, with evidence stemming from a man interred in York. By analyzing ancient DNA, researchers have connected genetic findings to historical records of Germanic, Roman, and Viking migrations, revealing intricate patterns of movement that influenced early medieval Europe.

In a study published in Nature, the researchers introduced a new data analysis method called Twigstats. This technique allows for a more precise measurement of differences between genetically similar groups, uncovering previously hidden aspects of global migration.

This groundbreaking approach has revealed new insights into European migrations, providing a clearer understanding of the movements that have shaped the continent’s history.

The researchers applied their new method to analyze over 1,500 European genomes, representing individuals who lived mainly during the first millennium AD (from year 1 to 1000). This period includes the Iron Age, the decline of the Roman Empire, the early medieval ‘Migration Period,’ and the Viking Age.

Their innovative approach concentrated on genome mutations that occurred within the last 30,000 years, rather than considering all genetic variations between populations. This focus enabled a more detailed investigation of the relationships among genetically similar groups. By honing in on these relatively recent mutations, they could compare genetically similar populations with greater accuracy.

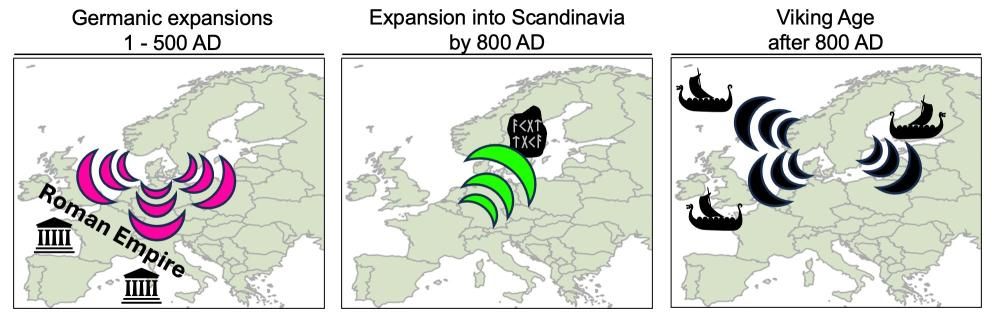

The Romans, whose empire was thriving at the beginning of the first millennium, documented their conflicts with Germanic tribes beyond the Empire’s borders. Genetic evidence supports that groups from Scandinavia and northern Germany migrated southward during the early Iron Age. These migrations introduced Scandinavian ancestry into regions such as southern Germany, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, and southern Britain.

Notably, researchers uncovered an individual from southern Europe who was entirely of Scandinavian descent. This finding supports the idea that the dissemination of Germanic languages and genetic intermingling had a considerable effect on the populations of Roman Europe.

Among the most striking discoveries is a man interred in Roman York between the second and fourth centuries CE, who was found to have 25% Scandinavian ancestry. Researchers suggest that he may have been a gladiator or an enslaved soldier, indicating that Scandinavians had been present in Britain for centuries before the Viking invasions. This challenges the commonly held belief that Scandinavian influence only began during the Anglo-Saxon or Viking periods.

The second wave of migration occurred between 300 and 800 CE, involving movement from Central Europe into Scandinavia. The genetic analysis of Viking-era remains in southern Scandinavia shows a mix of local and Central European ancestry, suggesting a significant influx of genes just before the onset of the Viking Age.

This is further supported by archaeological evidence; findings in Sweden indicate that migrants from Central Europe not only settled in the area but also established families there. This migration reflects a long-term shift in Scandinavian ancestry rather than a singular event. Researchers propose that ongoing conflicts in the region may have contributed to these migratory patterns.

Europe was the scene of numerous raids and settlements during the Viking Age (c. 800–1050 CE). According to genetic evidence that supports historical records, Viking-era people in Britain, Ukraine, and Russia have Scandinavian ancestry. Due to their involvement in raids or military expeditions, some Viking remains found in British mass graves had direct genetic ties to Scandinavia.

Leo Speidel, lead author of the study, emphasizes that Twigstats provides an unprecedented ability to analyze subtle genetic shifts over time. “Twigstats allows us to see what we couldn’t before, in this case migrations all across Europe originating in the north of Europe in the Iron Age, and then back into Scandinavia before the Viking Age. Our new method can be applied to other populations across the world and hopefully reveal more missing pieces of the puzzle.”

Peter Heather, a co-author and medieval historian, notes that historical texts often hinted at migration-driven transformations in Europe.

“Historical sources indicate that migration played some role in the massive restructuring of the human landscape of western Eurasia in the second half of the first millennium AD which first created the outlines of a politically and culturally recognizable Europe, but the nature, scale and even the trajectories of the movements have always been hotly disputed. Twigstats opens up the exciting possibility of finally resolving these crucial questions.”

Speidel, L., Silva, M., Booth, T. et al. High-resolution genomic history of early medieval Europe. Nature 637, 118–126 (2025). doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08275-2

Cover Image Credit: Part of the Zliten mosaic from the 2nd century AD showing gladiators. Photo: Wikipedia

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply