Why does Troy appear like an isolated outpost at the very top of the north-eastern Aegean when the cultural events of the time were much further south, namely in Minoan Crete and within the Mycenaean culture at the southernmost extremity of the Balkans? Who did the Trojans actually count as their neighbors? How should one imagine the settlement on the Anatolian side of the Aegean around 1200 BC? Was there an independent culture there or was it an economically and politically wasteland, so to speak?

Anyone interested in the Aegean Bronze Age would probably agree with the definition of some archaeologists that “that which comprises Aegean prehistory is perhaps largely unproblematic: the prehistoric archeology of mainland Greece, the Aegean islands, and Crete.” However, this definition leaves out two-thirds of the Aegean coasts, namely the entire east and north shore. So there is a need for action here.

For thousands of years, the majority of western Asia Minor was politically fragmented into many petty kingdoms and principalities, possibly due to its vast extent and complicated topography. This weakened the region’s economic and political importance, but it also slowed the recognition of a more or less consistent Luwian culture.

The Luwian culture thrived in Bronze Age western Asia Minor. It has thus far been explored mainly by linguists, who learned about Luwian people through numerous documents from Hattuša, the capital of the Hittite civilization in central Asia Minor.

In formerly Luwian areas, very few excavations have so far been made. As a result, Luwians have not been considered in historical reconstructions by excavating archaeologists. The collapse of the Bronze Age cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean can be explained more plausibly once Western Asia Minor and its inhabitants are taken into account by Aegean prehistory.

From a linguistics point of view, however, the Luwian culture is relatively well known. From about 2000 BCE Luwian personal names and loanwords appear in Assyrian documents retrieved from the trading town Kültepe (also Kaniš or Neša). Assyrian merchants who lived in Asia Minor at the time described the indigenous population as nuwa’um, corresponding to “Luwians.”

At about the same time, early Hittite settlements arose a little further north at the upper Kızılırmak River. In documents from the Hittite capital Hattuša written in Akkadian cuneiform, western Asia Minor is originally called Luwiya. Hittite laws and other documents also contain references to translations into “Luwian language.”

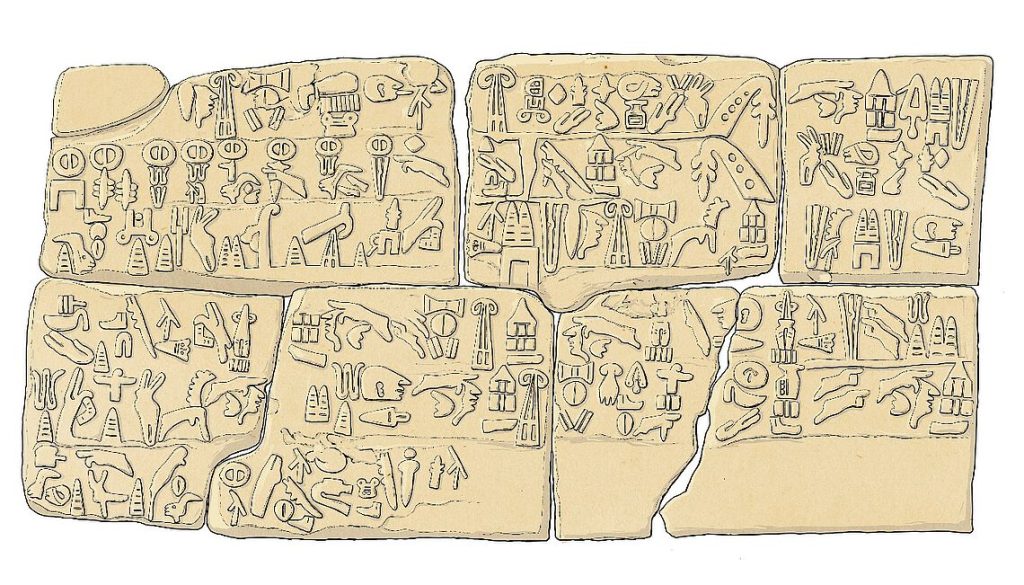

Accordingly, Luwian was spoken in various dialects throughout southern and western Anatolia. The language belongs to the Anatolian branch of Indo-European languages. It was recorded in Akkadian cuneiform on the one hand, but also in its own hieroglyphic script, one that was used over a timespan of at least 1400 years (2000–600 BCE). Luwian hieroglyphic ranks, therefore, as the first script in which an Indo-European language is transcribed. The people using this script and speaking a Luwian language lived during the Bronze and Early Iron Age in Asia Minor and northern Syria.

The term “Luwian” is now widely used to refer to a language, a writing system, and an ethnolinguistic group that could speak either one or both of those things. The term “Luwian” is frequently used to refer to people who lived at the eastern end of the Mediterranean during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE because the majority of Luwian hieroglyphic documents have so far been discovered in Early Iron Age Syria and Palestine. However, the Luwian hieroglyphic script can also be found in western and southern Asia Minor as early as 2000 BCE. Therefore, the term Luwian is also applied to the indigenous people who lived in western and southern Anatolia – in addition to the Hattians – prior to the arrival of the Hittites and during the Hittite reign.

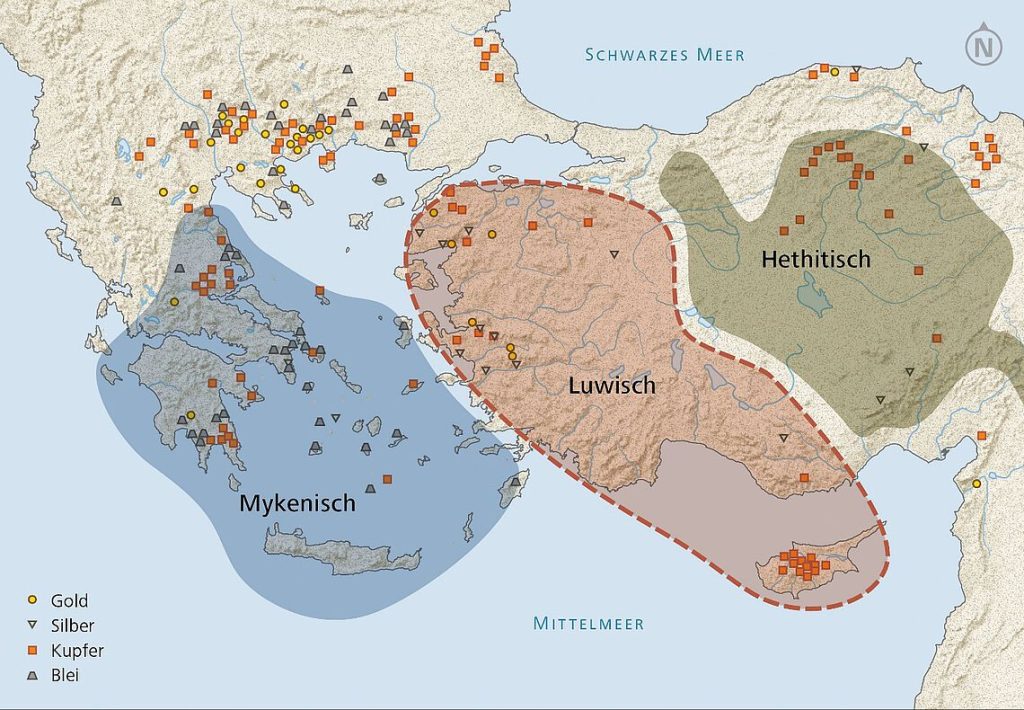

The results now published fully confirm the existence of a distinct Luwian culture between Mycenaean Greece to the west and the Hittite kingdom to the east. This Luwian culture extended over a larger territory and also existed much longer than the cultures of their well-studied neighbors, the Minoans, Mycenaeans, and Hittites.

The Luwians had their own hieroglyphic script, which had been in use for 500 years before the Mycenaean Greeks – just a stone’s throw away – first learned to write. Even after the downfall of the Bronze Age cultures, around 1200 BC, the Luwian hieroglyphic script remained in use throughout the Dark Ages until around 700 BC. In these centuries the knowledge of writing in Greece had been completely lost. More Luwian settlement sites are already known today than from the neighboring regions that have been researched for a long time.

A Luwian king corresponded with the Egyptian pharaoh, which, as far as we know, does not apply to any Mycenaean king. The recognition of an independent Luwian culture also explains the later rise of the Lycians, Lydians, and Carians in western Asia Minor, whose languages turn out to be Luwian dialects. The Luwian culture of the Late Bronze Age apparently provided the substrate on which the later cultures of the Early Iron Age could thrive.

For the locations of settlements, the Luwians preferred the edges of the fertile flood plains, which are much larger in western Asia Minor than in Greece. So farmers lived right next to their farmland, in places where fresh water was plentiful. The inclusion of the presumed transport network in the GIS analysis shows that a good half of the settlements were less than four kilometers from a thoroughfare.

Only in a few strategically important places did the rulers erect fortifications with mighty protective walls on hills. It is not yet possible to say whether these were barracks or places of refuge for the population. To date, there is no capital with the administrative seat of a local ruler, which is why no archive has yet been found. However, there have not been any large-scale excavations to date.

Politically, the Luwian countries formed a patchwork quilt of states and small kingdoms, which at times competed with one another, but also repeatedly formed alliances, especially for military purposes. Troy functioned as a border city with Thrace, whose culture differed significantly from that of Luwia. In the thirteenth century BC, Troy developed into a hub for long-distance trade, particularly with Cyprus and Syria.

A characteristic feature of Luwian warriors seems to have been feathered crowns. Fierce-looking attackers with such conspicuous headdresses appear on painted vessels at Luwian settlement sites; but they are also found on the back of the famous Mycenaean warrior vase, which apparently shows the enemies of the Greeks in the Trojan War. In the important Sea Peoples inscriptions on the mortuary temple of Ramses III. crowns of feathers are the most distinctive feature of the attacking warriors. This may be an indication that the Mycenaeans in the Trojan War and the Egyptians in the attacks of the Sea Peoples had the same enemy: namely the Luwians from western Asia Minor.

Using a geographic information system researchers at the foundation Luwian Studies for the first time recorded and evaluated 340 settlements of the 2nd mill. BCE in western Turkey.